This week I was asked to look at a “grandfather” clock. It turned out to be a French comtoise or morbier clock in a very tall case.

Comtoise clocks were made in large numbers in the vicinity of Morbier in the Franche -Comté region of France, near the Swiss frontier, from the late 17th century to the beginning of the 20th. They are sometimes called Morez clocks or Morbier clocks, from place names in the area. In the 19th century they were to be found far and wide across France, virtually ousting all other local clock making traditions. They were often marked with the name and town of the seller rather than those of the maker.

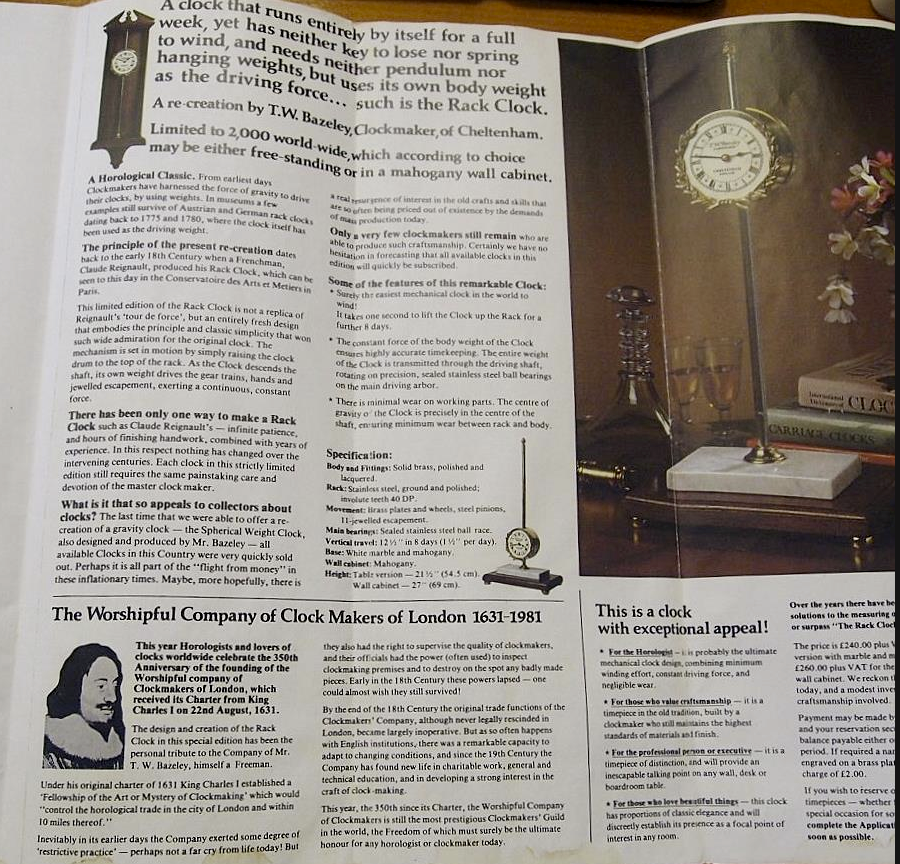

Here’s a picture of the dial:

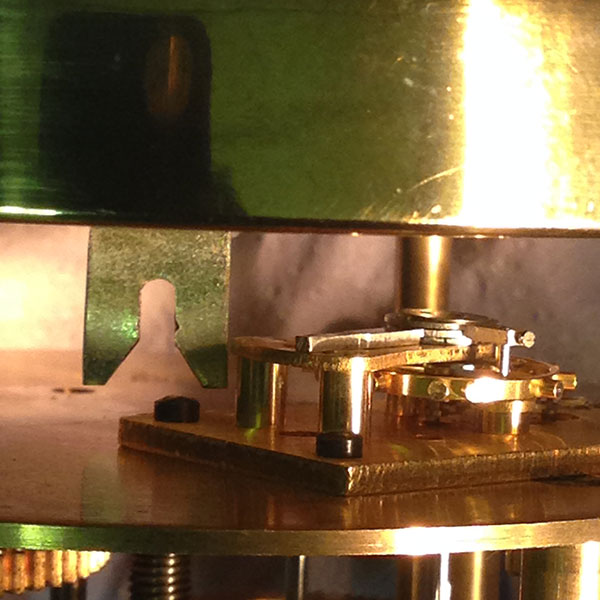

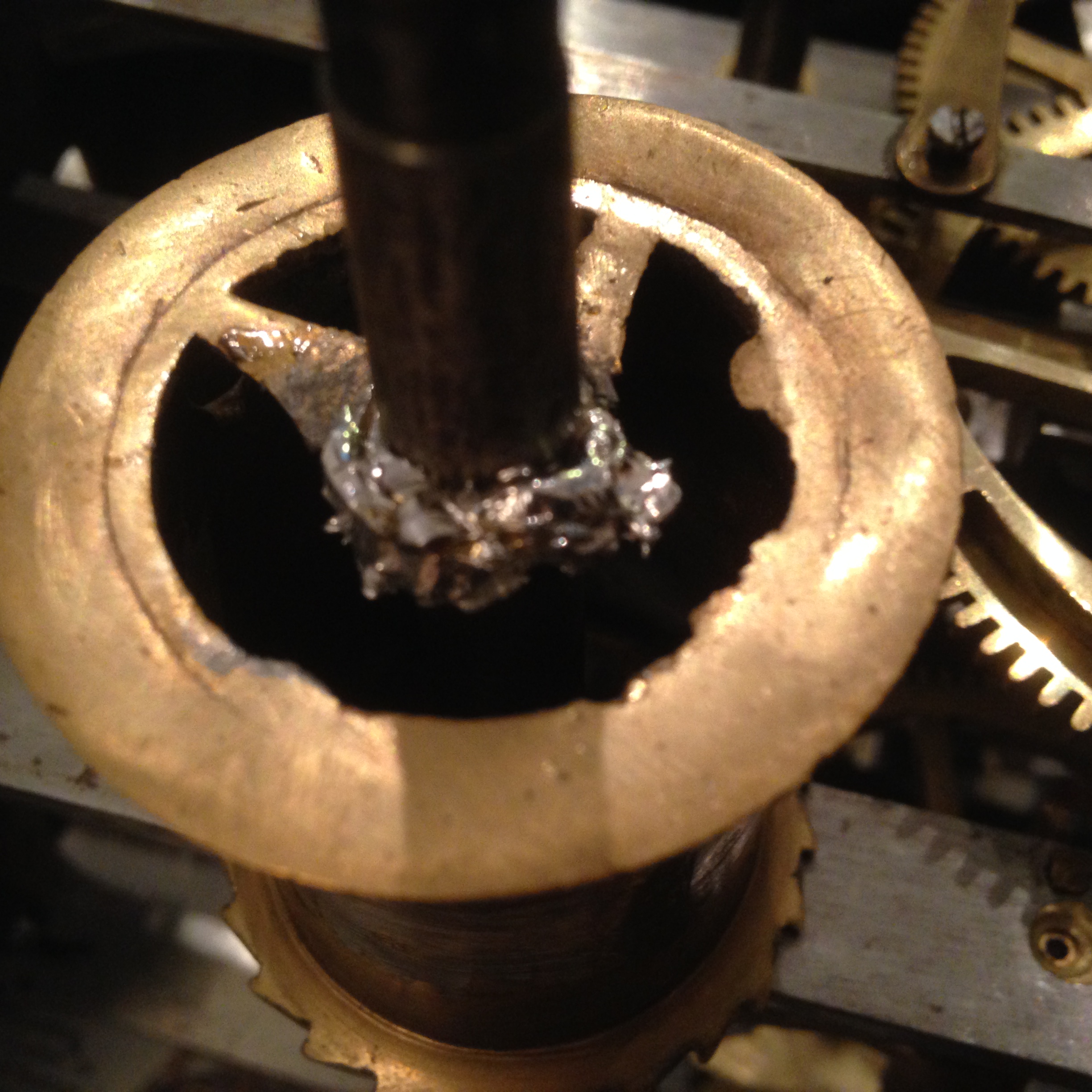

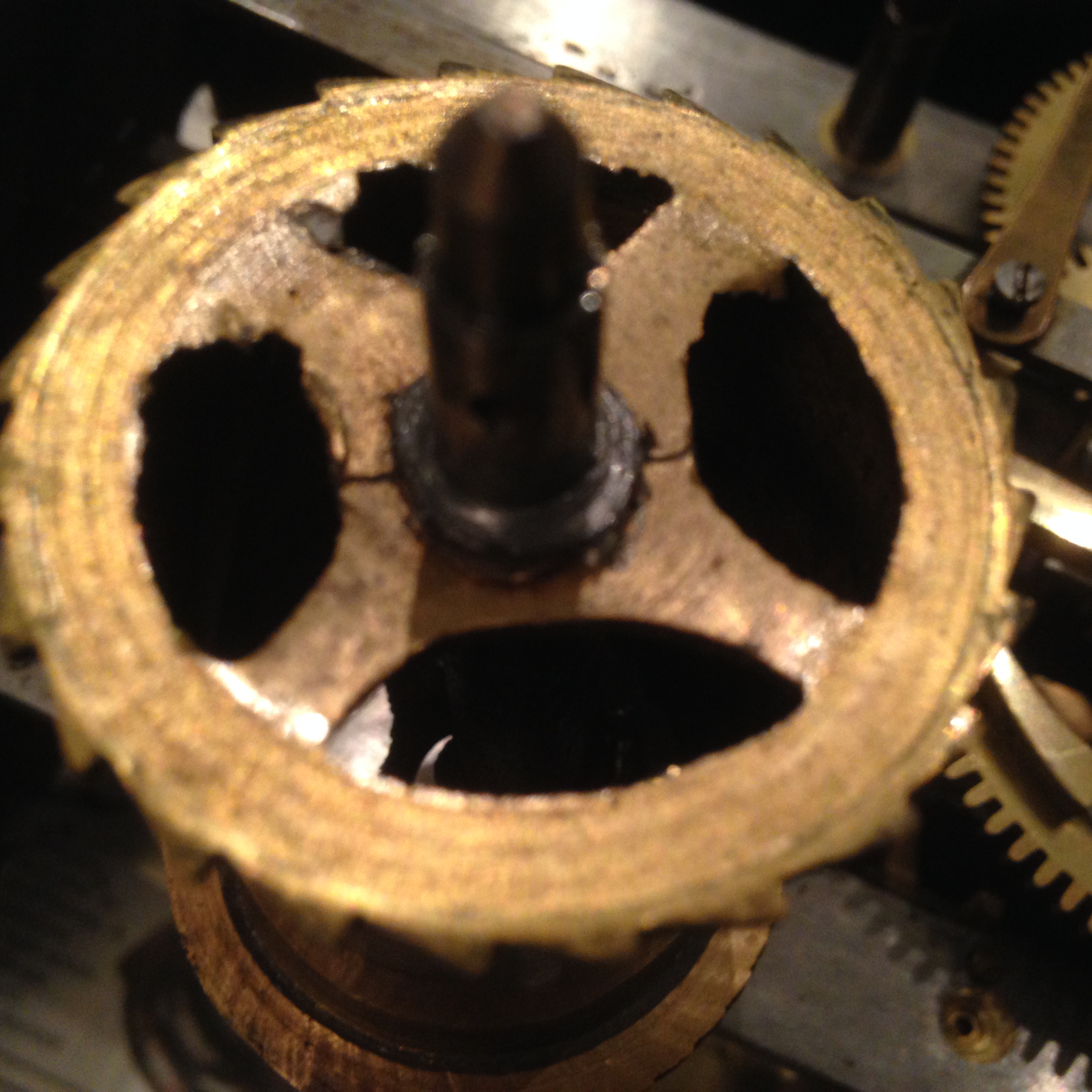

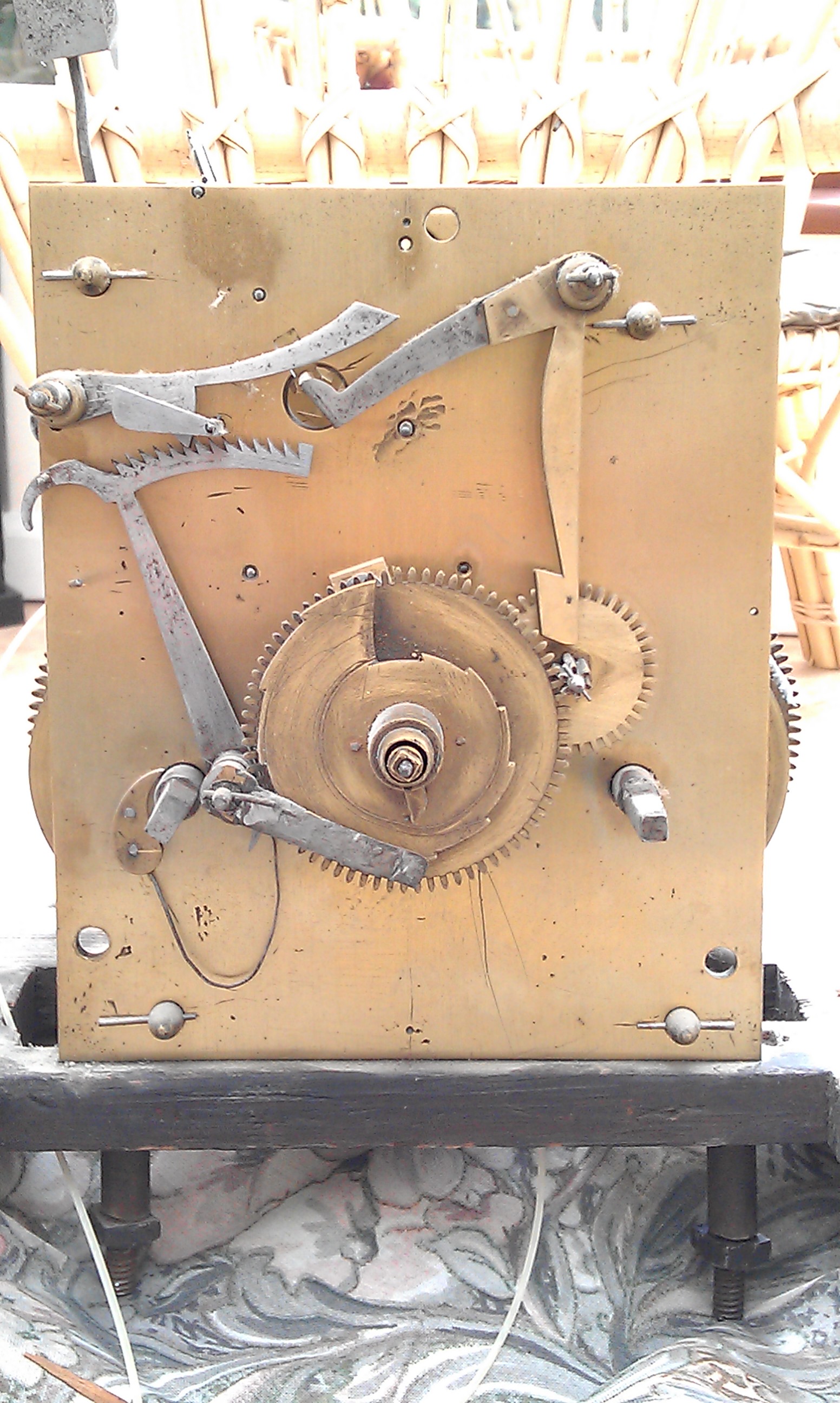

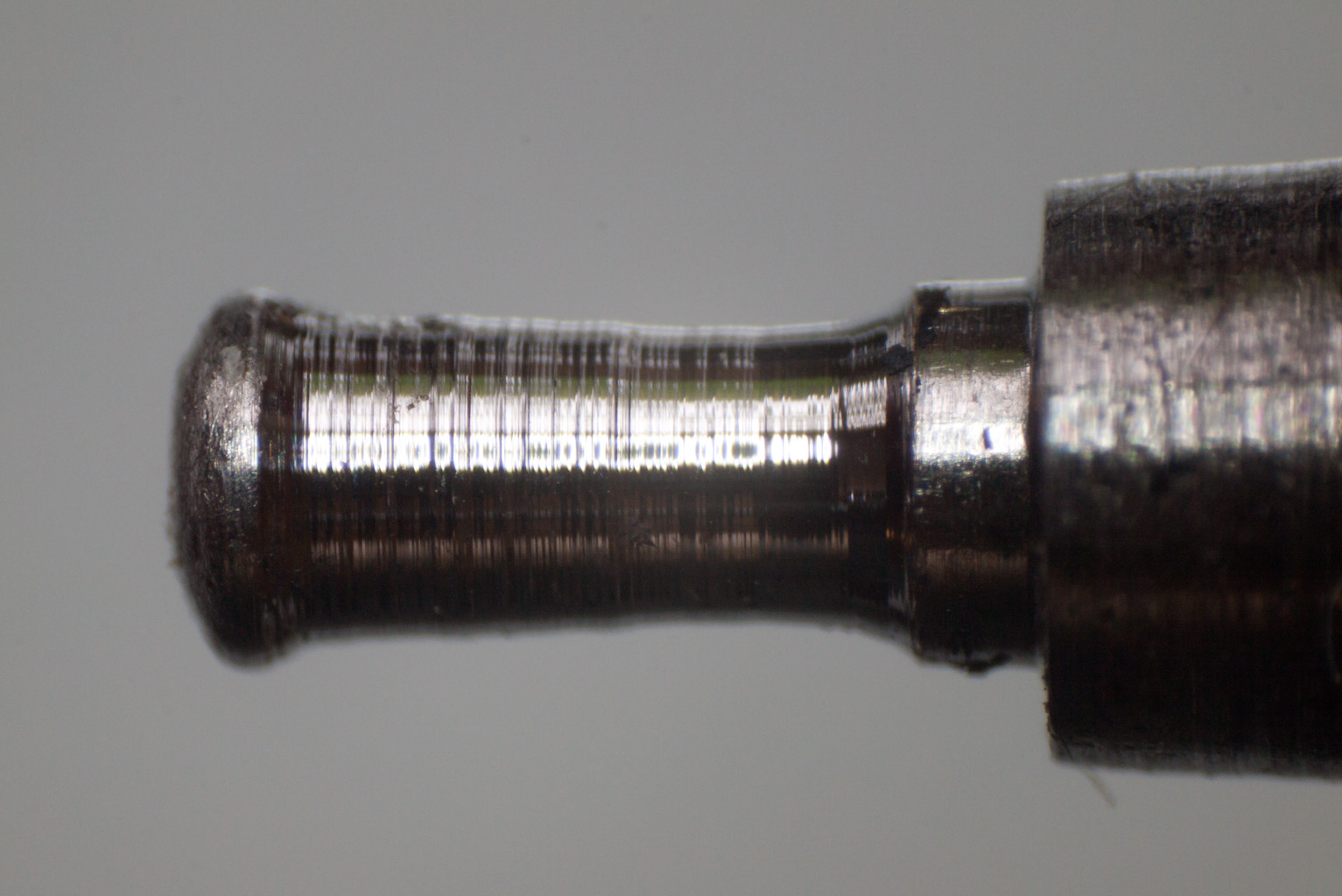

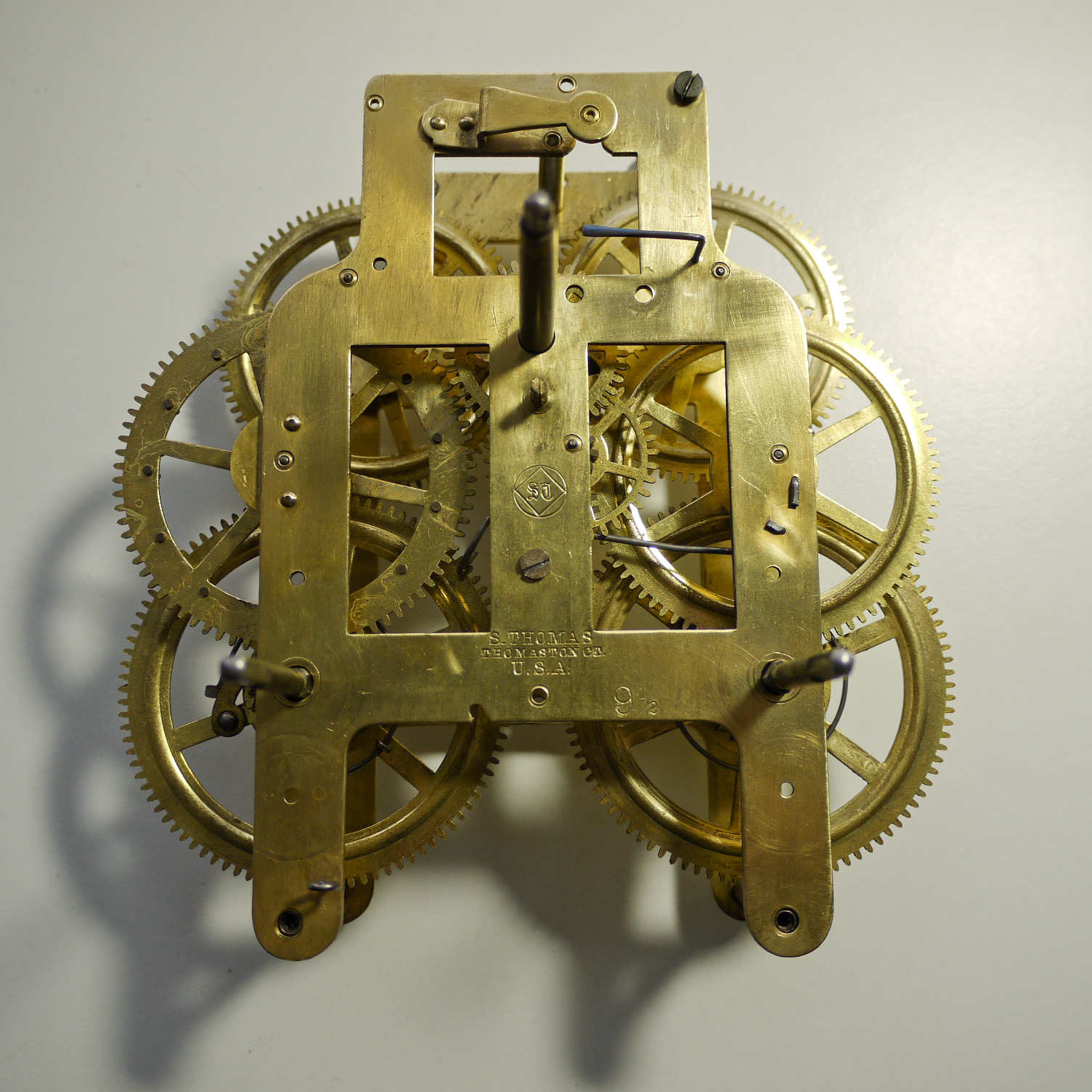

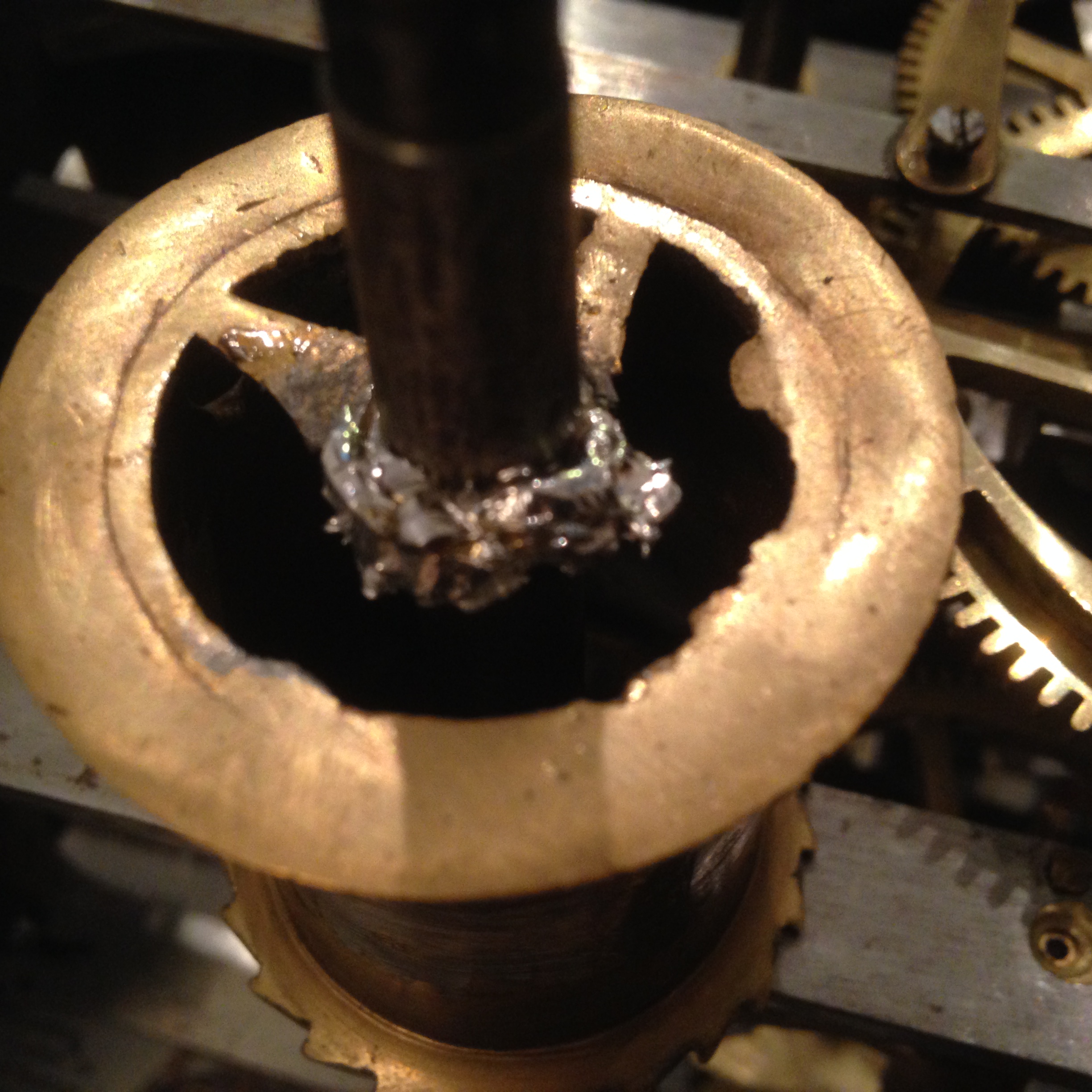

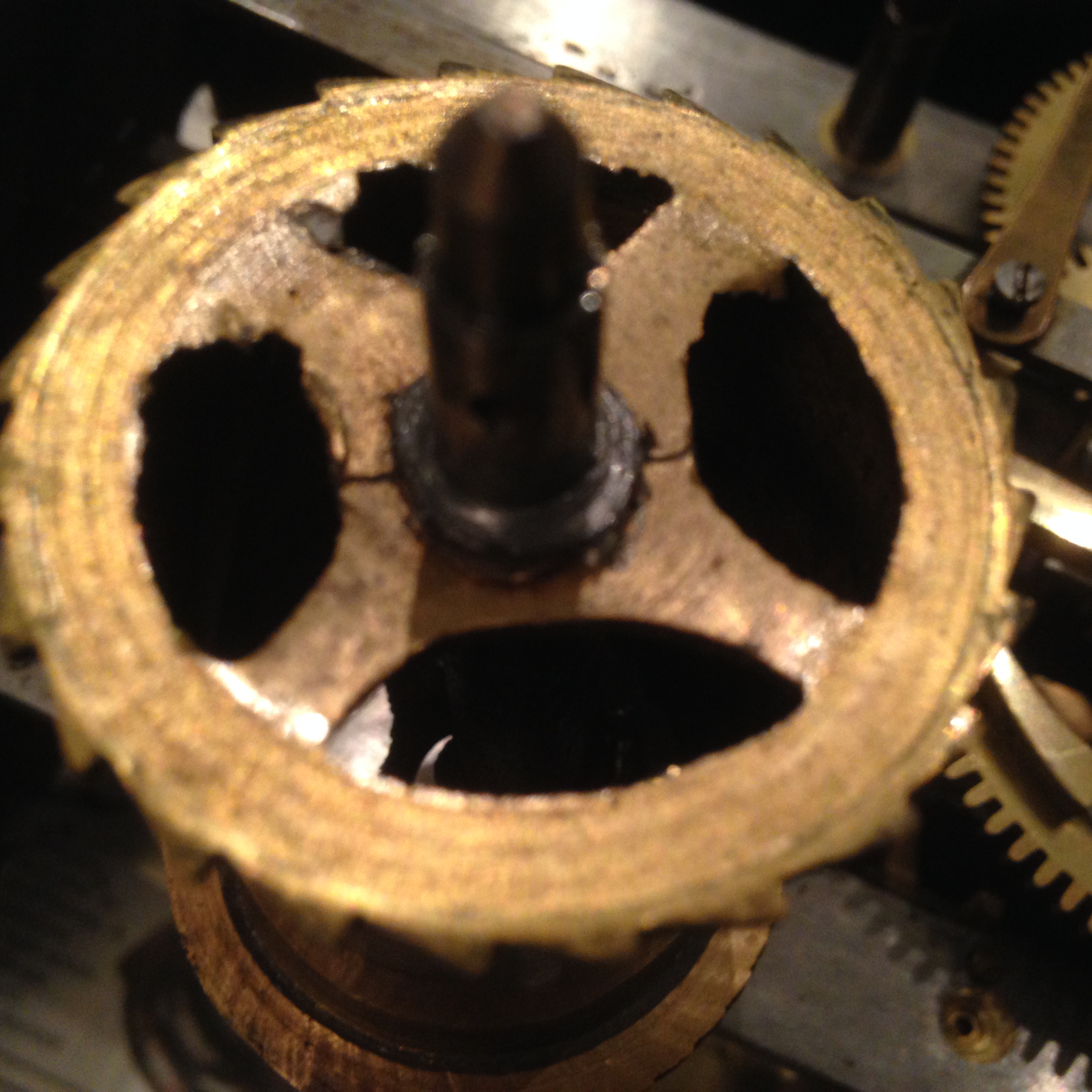

The clock had suffered a catastrophic failure of the strike train winding barrel. The end plates of the barrel appear to be castings, with the barrel itself probably rolled and soldered into the end plates. This assembly is also soldered to the barrel arbor. The casting had fractured, and the owner had attempted to re-solder it to the arbor, but the strength of the strike weight had been too much for the joint.

There would seem to be two possible courses of action, either make a completely new barrel, or repair the broken one, using as much of it as possible. I’m still debating the pros and cons of both, and I’ve also posed the question on the NAWCC forum.

Some history

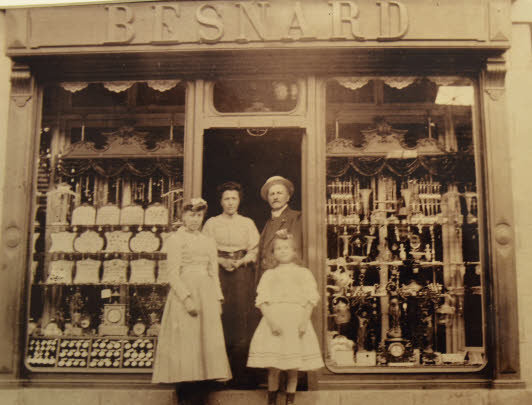

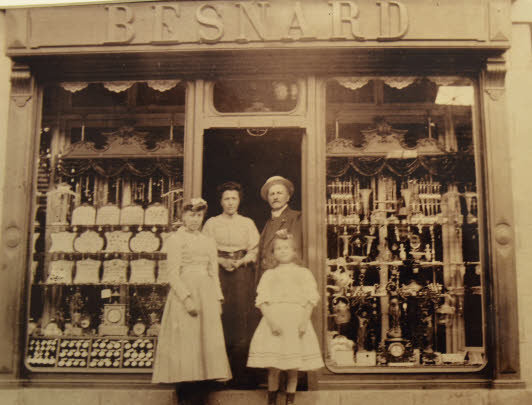

Chateaulin is a town in Brittany, north-west France, and a search for Besnard, clockmaker, threw up some interesting history. Lucien Besnard opened a shop (a jewellers, or bijouterie) in the rue d’Eglise in Chateaulin in 1850, and the shop is still there today, still in the family (screenshot from Google Streetview):

The story appears on a french website http://www.letelegramme.fr/local/finistere-sud/chateaulin-carhaix/chateaulin/bijouterie-depuis-163-ans-dans-la-famille-04-02-2013-1993820.php with a photo of the shop taken about 1910:

Here is the french text of the article:

Fondée en 1850, la bijouterie de la rue de l’Église est sans doute le seul commerce châteaulinois à avoir perduré aussi longtemps dans la même famille. Gilles Rault, l’arrière-petit-fils du fondateur, en a conservé la mémoire.

Mon arrière-grand-père racontait qu’il y avait des files d’attente sur la place pour venir acheter ses fameuses horloges comtoises. Et que les charrettes, bloquées, faisaient la queue sur le pont ». C’était au XIX e siècle et déjà le franchissement de l’Aulne ne coulait pas de source. Du moins à en croire Lucien Besnard, l’aïeul de Gilles Rault. « Dans la famille, il se disait qu’il avait parfois tendance à en rajouter », tempère le bijoutier de la rue de l’Église. « Il soutenait aussi que, lorsqu’il ouvrit sa boutique en 1850, il était le premier bijoutier horloger du Finistère ». Marie-Thé Rault, l’épouse de Gilles, en doute. « Quand même, il devait bien y en avoir d’autres à Brest ou à Quimper.

Mariage arrangé

Quoi qu’il en soit, Lucien Besnard était un précurseur. Et pas seulement dans l’horlogerie ou la bijouterie. Il était aussi opticien et vendait des cuillères de mariage, très en vogue à l’époque. « Mon arrière-grand-père était originaire de Normandie. Son frère et lui s’étaient mariés avec deux soeurs. Un mariage arrangé, comme c’était souvent la coutume, par les représentants qui sillonnaient la France pour placer leurs marchandises. Ils en profitaient pour mettre en relation les candidats aux épousailles ». En se mariant avec Marie Digne, Lucien Besnard débarqua donc dans la cité de l’Aulne en 1850. « Il y fit bâtir l’actuelle maison où se trouve toujours notre bijouterie ». La rue de l’Église regorgeait alors de commerces. D’anciennes photos, conservées par la famille, attestent de la présence d’un tabac, attenant à l’actuelle bijouterie, et plus haut, d’une librairie.

Maison de confiance

Gilles Rault a aussi conservé une ancienne publicité. À l’époque, on n’y allait pas de main morte dans la « com ». « Habitants de la ville et de la campagne, mettez-vous en garde contre certains marchands peu scrupuleux qui vous exploitent en vous vendant du doublé pour de l’or », claironne la pub de la Maison Besnard. Une « maison de confiance », où l’on pouvait acquérir une montre en or pour « 50F ». À la mort de Lucien, en 1921, son fils Eugène, lui succéda. « Tout en conservant l’activité historique de son père, il développa l’affaire en vendant des phonographes, et leurs aiguilles qui s’usaient si vite, mais aussi des postes de radio, des machines à coudre, des stylos plumes… ». La fille d’Eugène, qui, à 85 ans, a toujours bon pied bon oeil, épousa André Rault, le père de Gilles, aujourd’hui disparu. « Un temps, la boutique a associé les deux noms, Besnard et Rault, pour finir par n’en conserver qu’un seul. Puis, mon père a surtout développé l’optique, activité qui fit sa renommée ».

Qui prendra la relève ?

L’optique, Gilles Rault l’a abandonnée en reprenant l’affaire familiale en 1973. Après six années passées à se former à l’école d’horlogerie de Dreux, puis celle de bijouterie à Besançon, « l’artisan » s’est recentré sur les métiers d’origine de la famille. Avec sa femme, ils ont aussi suivi des cours à l’école de gemmologie de Rennes, pour tout savoir sur les pierres précieuses. Et si Gilles Rault ne vend plus d’horloge comtoise, il sait toujours les réparer. « À une époque où le jetable a pris le pas, les artisans sont devenus des dinosaures ». Des dinosaures qui vendent aussi sur internet. Les temps changent. Quant à la succession, les enfants de Gilles et Marie-Thé ont choisi une autre voie professionnelle. « Peut-être que nos petits-enfants prendront la relève ».

© Le Télégramme – Plus d’information sur http://www.letelegramme.fr/local/finistere-sud/chateaulin-carhaix/chateaulin/bijouterie-depuis-163-ans-dans-la-famille-04-02-2013-1993820.php

And here is a translation:

Founded in 1850, the jewellers in the rue de l’Eglise is probably the only shop in Châteaulin to have lasted so long in the same family. Gilles Rault, the great-grand-son of the founder, tells the story.

My great-grandfather told that there were queues in the square to come in and buy its famous Comtoise clocks. And that carts, blocked, would line up on the bridge. ” It was in the nineteenth century and already crossing l’Aulne was not easy. At least according to Lucien Besnard, the grandfather of Gilles Rault. “In the family, it was said that he sometimes exaggerated,” cautions the jeweller in the rue de l’Eglise. “He also argued that, when he opened his shop in 1850, it was the first watchmaker and jeweller in Finistère”. Marie-Thé Rault, wife of Gilles is doubtful. “Still, there had to be others in Brest or Quimper.

Arranged marriage

Anyway, Lucien Besnard was a pioneer. And not just in watches or jewelry. He was also an optician and sold wedding spoons, very fashionable at the time. “My great-grandfather was from Normandy. He and his brother were married to two sisters. An arranged marriage, as was often the custom, by representatives who traveled around France selling their goods. They took the opportunity to introduce eligible men and women . ” By marrying Marie Digne, Lucien Besnard then landed in the city on l’Aulne in 1850. “There he built the present house which has always been our jewellers shop.” The rue de l’Eglise has always been full of shops and businesses. Old photos kept by the family show a tobacconists, adjoining the current jewellers, and above, a bookstore.

House of trust

Gilles Rault has also kept old publicity material. At the time, advertising was not subtle. “Inhabitants of the city and countryside, be on your guard against unscrupulous traders who exploit you by selling you gold at twice the proper price,” trumpeted the publicity for the House of Besnard. A “trusted shop,” where you could buy a gold watch for “50F”. On the death of Lucien, in 1921, his son Eugene, succeeded him. “While preserving the historic activities of his father, he developed the business by selling gramophones and their needles which wore so fast, but also radios, sewing machines, feather pens … “. The daughter of Eugene, who, at age 85, is still going strong, married André Rault’s father Gilles, now deceased. “One time the shop had the two names, Besnard and Rault, eventually only one. Then, my father especially developed optics, activity that made him famous. “

Who will take over?

Gilles Rault abandoned optics on taking over the family business in 1973. After six years at Dreux watchmaking school, then the jewelery school in Besançon, he refocused on the original family business. With his wife, they have also taken courses at Rennes gemology school to learn all about gemstones. And if Gilles Rault sells more comtoise clocks, he always knows how to repair them. “At a time when the disposable took precedence, artisans have become dinosaurs.” Dinosaurs that also sell online. Times change. As for the succession, the children of Gilles and Marie-Thé have chosen another career path. “Maybe our grandchildren will take over.”

The history of the shop and the style and details of the clock (anchor escapement, spring pendulum suspension) therefore dates it to shortly after 1850.